Barriers to Public Sector Innovation (Part 2)

This is the second part of a 3 part post on why innovation is so difficult to enact in the Public Sector. Part 1 can be found here: Barriers to Public Sector Innovation Part 1.

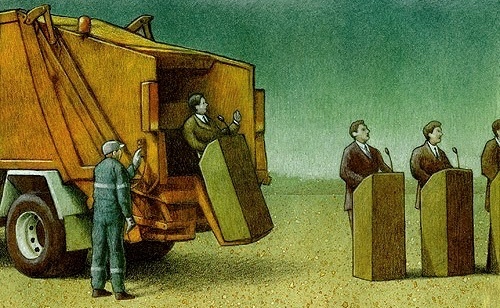

I’ve always been fond of the picture above. I’m unsure if the identical speakers pictured are being deployed en masse to deliver the same old tired messages or, being collected by a garbage truck and disposed of? Both interpretations work well for me.

Again, I don’t offer this post as an exhaustive list of barriers, merely a number of key ones that if addressed, or at least diminished, will allow Public Sectors the extra agility required to be more innovative.

I’ll again acknowledge the many public sector people who battle on, do great work and have great success in spite of these barriers. You resistance fighters know who you are …

9) Valuable and costly meetings are wasted

One of the most common questions I put to groups and teams is “A show of hands please, how many of you have had your time wasted in a meeting of late”? The response hardly varies, 90%+ of people in the room raise a hand and a gentle, almost embarrassed zephyr of laughter sweeps across the room.

Given innovation is reliant upon multiple and diverse perspectives from many people (preferably in the same room), meetings are important, yet we waste them. The old adage of many hands make light work whilst true in a physical labour sense, is exponentially more important in the knowledge and thinking fields. Two people working with a single physical task halves the burden whilst two people thinking on a mental issue doubles the output.

Whether it be innovation or any other organisational need, meetings are our lowest hanging fruit and yet the fruit is too often left to wither on the organisational vine.

In meetings we have the right people by virtue of an invitation and we have them in the ideal face-to-face setting in which the most meaningful communication can occur. Yet 90%+ of people attending meetings say their time is wasted.

It would be fascinating to measure the percentage of time spent in meetings across the board by all of our public servants and then based upon time spent and substantive wage levels of each calculate the cost of wages alone that meetings take up. The cost per Department would be astronomical. If meetings therefore could be reduced in time by a very conservative figure of 20%, the savings would be massive.

Other benefits of getting meetings right may even dramatically outstrip the fiscal benefits when one considers the improvements in decision-making, collaboration, meeting outcomes, staff engagement and the flow on to organisational culture.

Meetings that are driven by improved efficiency, improved process and focused on outcomes are pivotal to driving innovation.

More on how to achieve this in Barriers to Public Sector Innovation (Part 3) next month …

10) The F Bomb stops innovation in its tracks

Public Sectors have long suffered chronic Atychiphobia.

Ancient historian Herodotus once said “It is better by noble boldness to run the risk of being subject to half the evils we anticipate than to remain in a cowardly listlessness for fear of what might happen”. So, when that staff member comes up with that idea they believe will add value to our service delivery, instead of faltering and focusing on what will happen if it doesn’t work, we need to quickly design a way to test it in microcosm to find out if it can work or, … be reconfigured to make it work.

We seek to test in microcosm to ensure that if the idea does “fail” there is no damage done. This type of failure has a beneficial upside in that we potentially learn a valuable lesson in what we shouldn’t be doing and what we need to avoid going forward.

Sometimes knowing what will not work can be as beneficial as knowing what will.

Knowledge of those approaches that will not work it stops us traveling down costly and unproductive pathways.

Failure cannot continue to be thought of as a one size fits all concept. There are some very different types of failure and they are not all bad!

Let’s keep things simple and say that large scale failure is bad and just has no upside. A large scale failure usually involves a failed policy, process, programme or project that has used up a great deal of time and money. When everyone is being asked to do more with less we cannot afford this kind of large scale failure. Not only do large-scale failures damage us in an economic sense, they do tremendous damage to the public’s confidence in Government institutions.

Large scale failure has a negative impact on the organisation, its staff, its service delivery and the wider Public. Small scale failure however, manifests very differently and has multiple upsides.

I have scoured multiple Thesauri in search of a word that adequately describes small scale failure without the negative connotations of the larger version. I have found no satisfactory definition. We are stuck with the ‘F bomb’ so lets start to understand it in context and appreciate its value when it happens. Small failures can be beneficial, Big failures however are always BAD. Know the difference between the two and actively encourage and learn from the small.

Making critical assumptions about new ideas and dismissing them for fear of ending up on the front page of the Herald-Sun, or for fear of a negative response from a senior manager, does the Public a Disservice.

Innovation involves trialing lots of different ways of doing things and if you are not consistently failing in a number of these things you are simply not trying hard enough nor being inventive enough. When we are consistently experimenting with smaller short-term, low (or zero) cost approaches, we are proactively engaging with and learning about the environments within which we operate.

Do to otherwise is to sit, wait and have to react to whatever comes our way.

Government tends to be reactive and requires more simple, low-cost means of proactively engaging with the systems within which it operates. Sending a probe down that tunnel to make sure the light at the end is an exit, is a smarter way way of operating than advancing into the tunnel and discovering the light is that of a train barreling toward you.

Proactive short-term, low-cost experiments drives learning, builds agility and enables earlier engagement of issues before they land on our doorsteps and we are forced to react to them.

When we embrace small failures whilst trialing or prototyping new approaches, then that “failure” is a learning experience from which benefit can be derived. Failure needs to be seen, not as the opposite of success but as a key component of success.

The pathway to innovation is paved with ongoing and iterative failures.

By starting to think about, and approach the failure in a more constructive and less fearful light, there is an automatic flow-on that positively impacts another major barrier to Public Sector Innovation that is one inextricably linked to “failure” – the dreaded ‘R’ word …

11) The R Word is an innovation killer

It’s only the ‘R Word’ that can match the ‘F Bomb’ in striking fear into the heart of the dedicated bureaucrat.

Because of this, the public sector focuses very strongly on the assessment and avoidance of all kinds of Risk.

Risk Assessment is the application of critical assessment to determine those factors that might place the organisation and those in it’s charge in some kind of danger or at a disadvantage. Risk is right on top of the list of considerations when deciding on a ways forward for the sector … and quite rightly so.

Risk assessment is crucial, but it's not enough.

The safety and well-being of those the Public Sector engages with is paramount in every instance, so it’s little wonder that Risk and the critical thinking associated with identifying it, often dominate thinking to the exclusion of other thinking.

Another reason we focus so strongly on Risk Assessment is because we are programmed to do so – we are all quite brilliant risk assessors! A quick risk assessment of any given situation is a great way to stay safe.

In a not so distant past, risks in our environment were a major factor shaping the way our brains evolved. Our ancestors needed to have a very strong focus on risk because doing so literally kept them alive in a world fraught with danger. Risks that by and large, we don’t have to contend with today.

Unfortunately, we bring those same instincts and programming into our modern organisational settings where we continue to apply our brilliant risk-assessing prowess in ways we do not even realise. Let’s use a hypothetical situation to illustrate the point.

A person hasn’t eaten for five days and they are literally starving. They are the first to arrive at work and sitting on the lunchroom table is a very attractive looking gourmet sandwich. What do they do? Given the circumstances we’d assume they would immediately pick it up and devour it. Not so. The first thing they do is a risk-assessment. How fresh is the sandwich? Who might it belong to? What would happen if I get caught eating it? How long will I have to eat it before someone comes in? How would my reputation suffer if caught? This is done almost unconsciously in the blink of an eye – risk assessment comes to us very naturally. In many of our modern organisational contexts however … too naturally.

We have whole business units and job descriptions dedicated to Risk-Assessment. We have dedicated teams and specific roles tasked with risk assessment and the seeking out and avoidance of those things that may do us harm. To date however, I have not seen a single business unit or job description named and tasked to undertake the essential thinking that is both complementary and essential to apply alongside risk assessment. Value Assessment.

Risk and Value are both sides of the same coin yet we focus primarily on the Risk side. (NB: I note some risk practitioners are doing this now and doing it well, but many do not.)

When we focus on risk and do not first consider potential value, it becomes very difficult for any new idea or approach to survive beyond the first utterance of “That will never work here”.

Too many times we have new thoughts, concepts and ideas shot down in the first instance because we tend to default to critique, before considering the potential value should the idea be implemented. New innovative ideas are too easily dismissed and there are many ways to dismiss them. I have seen potentially great ideas dismissed in an instance with a simple raised eyebrow of a senior person or dominant personality in attendance.

It's very easy to say NO to a new idea without having to say no.

When new ideas and concepts are untried and unknown our risk-programming kicks in. We see the new and unknown as potential threats and view them largely through our risk lens. When we apply this lens first, it’s often too late to consider the associated values because the idea has been effectively killed off.

Dismissing new approaches out of hand is an innovation killer.

In 99.999% of instances that strange noise you hear late at night while you lie in bed is not an intruder come to murder you, it’s simply something innocent from a far less threatening source. Yet, in most instances we become cautious and consider the worst even against that 00.001% chance.

In a danger filled world where we once literally had to look over our shoulders to survive,viewing everything through a lens of risk first is a great way to stay safe. It’s not however the ideal default-thinking for new ideas and concepts developed inside our organisations.

12) Accepting outputs instead of outcomes means innovation struggles

Outputs are easy, outcomes are hard. Too often the sector focuses on the outputs determined and not the outcomes needed.

The assumption that if we achieve certain outputs and targets, the outcomes sought will automatically follow, is an erroneous assumption.

At the request of a friend I attended a tender briefing in a Government Department over a significant leadership programme. During the initial briefing from the Department the focus was on procedural matters and expected outputs. No mention of the programmatic outcomes was made. What we found even more disturbing was that during questions none of the 20+ consultants and potential service providers asked a single question about what outcomes they were expected to produce should they win the tender. Again, the questions all revolved around detail and procedure. The focus was on the boxes that needed to be ticked.

Many Learning & Development initiatives provide good examples of the focus on outputs rather than outcomes. Learning programmes are often run as “tick the box” exercises with no serious expectation or demand for the timely, practical and measured application of the learnings by participants on real world issues.

The default defensive position adopted against this argument is that some training is around personal development and can’t be measured. The measurement and metrics therefore need to be key components of the training design itself, because if there are no demonstrable results the training is wasted, the participant’s efforts are wasted and the public purse is wasted.

It’s very easy to tick a box and say this year we trained 500 people in MBTI but another thing altogether to demonstrate the value it afforded the Department and the Public on whose behalf they operate.

When using public money there is a responsibility to be able to demonstrate outcomes. If we cannot demonstrate a link between the training and training outcomes, we should perhaps consider whether or not we should be offering that training at all.

Without mandated application there can be no demonstrable measurement of any outcomes. All we end up with is a target achieved, a box ticked and the public purse diminished.

N.B. I’m not singling L&D out here, it’s just that training often provides many examples of focusing on outputs rather than evaluated outcomes. Ticking boxes is common in many areas of Government.

13) Assuming A+B is going to = C is not how innovation happens

The world has become inextricably connected and is shifting and changing at rates that make it very difficult to be able to say “I know the cause of this and I know how to fix it”.

Yet, with paradigms that still revolve around top down imposed order and control, the Public Sector still tends to default to approaches that are better suited to a static, more predictable and knowable world. New thinking and innovative approaches are needed that are not based on erroneous assumptions of “Expertise” and “knowing what to do”.

No one however gets recruited or a promotion based upon “not knowing what to do” because we seek certainty in all things. Certainty of process and outcome is in reality a very rare concept, yet this paradoxically is what we tend to seek and base our decisions upon.

“The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt” (Bertrand Russell)

I stated in Part 1 of this topic that bureaucracies are by definition about control, and why not? When you are dealing with crucial areas such as Health, Justice, Social Security & Child Protection, control is a GOOD thing to have. We demand that Government maintain control over these challenging areas on our behalf because without it we’d be in big trouble.

Herein lies the fundamental issue, and it’s all about the “control” we seek. The most difficult and vexing issues Government needs to address cannot be controlled completely as they are inherently complex and shifting. The goal posts here are moving constantly.

Control measures assuming cause and effect relationships where cause and effect cannot be immediately perceived will in most instances, fail.

When we approach an issue that is essentially complex and shifting and believe we can make assumptions based upon what might have happened in the past, we tend to get things wrong. Throwing assumption based interventions at problems that are multi-faceted and shifting do not work. Not only do they mean tremendous waste, but they also produce unintended and unforeseen consequences. Our Federal Alcopop Tax developed to tackle underage binge drinking is a classic case in point. There was a chasm between the assumptions of how it would play out and how it actually did play out.

If we concede that A+B does not always =C then we have to be able to safely concede that we are uncertain. Uncertainty however, is an uncomfortable position to find one’s self in when you have serious public responsibilities to discharge. The expectations placed upon public sector staff to be certain and always get things right only makes this uncertainty more uncomfortable.

A new idea or a new way of doing things is by definition “novel”, and to start to address our most pressing intractable issues we are going to need novel approaches. Unfortunately, bureaucrats who are focused strongly on structure, order and certainty tend to reject novel ways forward as they are not in accordance with their thinking or patterns of past experience.

Even when an innovation happens in Government (and innovation does happen in Govt) many still tend to reject the approaches applied in finding it by saying the end innovation is purely logical and therefore they didn’t need any novel approaches to achieve it.

All innovations are 100% logical in hindsight. The means via which we arrive at them however are not!

To logically plot our way sequentially through assumption points to the answer of an intractable issue does not work and never has, except by pure luck. We require very different approaches that challenge our assumptions and force us to see perspectives other than our own to help break our existing thought patterns. We do this by generating non-linear, oblique or Lateral solutions. (More on doing this in Part 3.)

I have had lateral approaches rejected out of hand by senior public sector people and dismissed as “parlour games.” I’m pleased to say that that same dismissive Director actually participated in the lateral approach disguised as a logical one and produced an great outcome to what was a very challenging issue. They remained blissfully unaware of how the result was achieved but nonetheless happy they did things their logical way.

The most senior of bureaucrats do not know the answers, yet we defer to them as if they are all knowing. The manager that speaks and claims knowledge of always knowing what to do, and how to do it should raise red flags. On the other hand, the Manager that says “I’m unsure of how best to proceed, but I am going to try and find out” is the one more likely to succeed across a number of measures.

In another example of a non-linear approach we aided an Executive Officer group to apply a simple lateral thinking tool to identify 12.5 million dollars worth of hitherto unrecognised and measurable savings in a Government Department. This was done in a 3 hour session. That same Executive Officer group could not find any answers two weeks previous via conventional methods in a two day workshop. The lateral thinking approach applied allowed them to see issues from different perspectives beyond their own habitual ones. Non-linear, lateral approaches are deadly serious and essential business tools.

Linear and assumption laden approaches based upon the past can only tell us “what is and what was”. The road ahead is so different now we need innovative tools and methods that help us to design “What can be”.

A good example of innovative approaches to real-life issues in Government is (or sadly was) the Victorian Department of Health’s now defunct “Healthy Together Victoria” pilot programme. It has been well established that in the coming years we have a burgeoning health crisis approaching that some refer to as “diabesity”, the unholy alliance of diabetes and obesity.

There is a strong belief that this health crisis will be too great for our Health Departments to adequately address and manage. Therefore new thinking and approaches are required that involve getting the community itself to play a greater role in moving from a reactive-symptomatic approach to health (which falls to our health system to fund), to a proactive-preventative one managed within the community in which the illness does not manifest in the first place. A massive challenge to which there is no known answer.

Those involved in this project would routinely say they were uncertain as to how they would actually get there but they would say they were trying many, iterative approaches in an attempt to navigate their way to successful outcomes. This is an innovation mindset, one that does not automatically assume they have the answers but one that sets out to experiment and discover.

To their great credit, the Healthy Together Victoria people had managed to overcome the next barrier, a barrier that is not only common to the Public Sector but to almost every human being on the planet ….

14) Our “solution-0rientation” keeps us tunnel visioned

Humans are brilliant problem solvers. The Public Sector is full of great problem solvers. It’s a handy skill to have in the sector because of the complex problems faced in having a duty of care for entire communities. Our ability to make quick decisions based upon or knowledge and our patterns of past experience has made us a very successful species because doing so is a great survival mechanism.

As we discussed earlier, this tremendous capacity to reach into our patterns of past experience and pull out an answer based on the first matching pattern we find can detrimental to the task at hand. Our rapid solution-orientation is a skill more suited to a simpler set of problems and not highly complex and shifting public sector environment where issues are not as simple and shift over time.

Too often we proceed with too many assumptions and preconceived notions of what will work based upon past experience.

In a sense we are “straining at the leash” to provide an immediate fix, an immediate answer because we are wired to do so! Not only that, notices from he Secretary’s or Director General’s office demanding an answer to an issue by 5:00pm today means, they get an answer by 5:00pm!

Many feel uncomfortable stopping and making sense of an issue and exploring it from multiple perspectives when they believe they “know” the way forward. However, when the community’s welfare and the more expeditious use public money is paramount we need to be thinking very differently about how we address our problems.

My favourite quote from Albert Einstein sums up the approach required very succinctly:

“If the world was in dire peril and I had an hour to come up with an answer on how to save it, I’d spend the 1st 55 minutes thinking about the problem and only the last 5 minutes generating solutions”.

This is the antithesis of how most people operate (not just public sector people – Everyone)! This is the reason why programmes go off track, why interventions don’t work as well as planned, why projects go over budget. A very healthy percentage of issues faced are faced because we have inadequately stopped and taken the time to define the issue or opportunity from multiple perspectives and then, and only then start to consider alternatives, possibilities, choices and creative ways forward.

Just a few hours spent upfront applying structured problem definition approaches before launching to solution can save millions of dollars, thousands of hours and even lives down the track.

15) Innovation “strategies” do not work

All too often a strategy is developed and it stops dead there ….

Groups often sit around and discuss and debate the definition of innovation – this delays us moving to action and confuses the very objective of driving innovation. Depending on the context, an innovation for one may not be for another but the underpinning definition that lies at the core remains – an Innovation is something that is in some way new that adds measurable value.

There is no need to debate this!

To attempt to pidgeon hole an exact definition beyond this starts to limit where and how we might look for the innovative solution or opportunity and what form it might ultimately take.

Most organisations have one or more Innovation strategies sitting in a drawer that were either never implemented or failed during implementation. It’s a hard thing to do right. (I know from hard earned experience!)

I currently have a client who is requesting a 100 page “Innovation Strategy” document populated with lots of fancy words, convoluted graphics and those 5, 7 or 10 rules of thumb that will ensure innovation will take root. My response to date has been that this would be a waste of time and resources.

To start down the innovation route a more emergent approach is essential in which we systematically start to proactively engage with issues and opportunities in microcosm, via multiple small-scale approaches, measure the outcomes and leverage off the success and failures. i.e. Start the journey and draft the map retrospectively once you have experienced it, as opposed to drafting an imaginary map in hope. (An innovation strategy in itself I concede, but not the traditional one that is usually put forward).

A key component of any strategy is the iterative doing, learning and navigating based upon the learning. It does not involve a convoluted strategy document, expensive brochures & posters, online innovation hubs or idea software developed by https://goascribe.com/verbatim-coding-for-survey-research/. Nor does it involve those 5, 7 or 10 innovation rules that many love to dispense without knowledge of the unique contexts into which they might be applied.

Recipe based approaches and convoluted strategies tend not to work. When you see these artifacts of innovation – be skeptical!

Innovation comes about by doing first and strategising second based upon the learnings from the doing.

BTW …. there’s nothing worse than moaning about barriers and then disappearing without also offering some insight into how to address those same barriers. In the follow up to this article “Barriers to Public Sector Innovation – Part 3”, I am going to suggest a number of potential means via which organisations can start to side-step, diminish, remove or make irrelevant those barriers to innovation we are talking about!

This is great Frank. Very thought provoking and insightful. Can’t wait for Installment 3